Even though WB has shared his secret formula to investing, investors still can’t touch him. We’re going to take a deeper look into his tenets of investing, and see why no one can still touch him. I’m not a “value investor” per se, or a Buffett groupie, so I only discovered these 12 tenets after reading The Warren Buffett Way, by Robert Hagstrom. (Side note – I recommend this book to anyone who needs an introduction to Warren Buffett; but if you know his story, then you’re better off reading something deeper about Buffett and/or value investing. Update to this comment, The Snowball: Warren Buffett and the Business of Life by Alice Schroeder is a great in-depth biography of Buffett). Buffett’s 12 tenets fall into four broad categories and they are best followed in the order given because they start broadly and narrow down to the price you should purchase an undervalued company. Once you run down the list and find a tenet which isn’t copacetic with the investment in question, the stock fails the test and you can move on to the next one.

Completely irrelevant tangent (skip to next paragraph if you want to avoid it) – copacetic means satisfactory/in complete order, etc. I know this because I worked with a complete jackass who used words like this. This was more proof to avoid using fancy words when there is a simple one which will do just fine. This is an idea from Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People (#1 book I’d recommend for young professionals, or old ones who are jackasses). Conveying your ideas in the fewest and simplest words possible will make you look more intelligent than someone who uses ridiculous words in drawn out sentences. People who are impressed with fancy words are rarely the ones who are worth impressing. Warren Buffett is the epitome of this, and now back to his 12 tenets after that rant.

Revisiting the “…Trading Stocks” series which we’re in the midst of compiling, this would fit in perfectly as Part 3 – Fundamental Value Investing and How Buffett Does It. I’d like to avoid confusion of anything “Buffett” with the “How (not) to trade stocks” series. Buffett’s 12 tenets are broken into four categories: Business, Management, Financial, and Value. As mentioned, we’ll maintain order of the categories and tenets since it is vital to the filtering process. I must give a lot of credit to summaries.com which had a great PDF to refresh my memory of the tenets…and in a few cases I used its terminology directly – if it ain’t broke, then…copy it?

BUSINESS TENETS

1. Is the business simple and understandable?

If you don’t understand how the business works, don’t buy the stock. This notion seems intuitive enough to leave it there, but let’s think twice….no thrice. So many screw up at the very first of Buffett’s tenets, so we’ll take this a step farther. If you buy stock of EPIC computer but don’t how to build an EPIC computer, that doesn’t mean you don’t understand their business; likewise for an automobile, construction company, etc. Understanding the business translates to knowing how it makes money and why it will continue to do so going forward. If you understand why EPIC has superior manufacturing capabilities and how it is able to deliver a good product with exceptional customer experience, then at the least you are beginning to understand the biz. This means you understand its competitive edge, hence, why its market share will grow and revenues will continue to rise (revisit the importance of revenue growth here). Competitive edge is perhaps the simplest reason to invest in a stock. Financials, ratios, and other complicated company valuation talk matter less if you grasp how the company makes money and why it will continue to grow going forward.

Giving it thrice the thought, comparing EPIC to the example Buffett might use would show the essence of simple and understandable businesses. WB bought Coca-Cola (KO) way back when because their product was the best and once you were hooked you couldn’t stop. Buffett was already addicted to Coke so he knew he’d be a customer forever. I mean, they actually had cocaine in it until the early 1900’s. When Buffett first invested there was no cocaine….but c’mon, this company was smart enough to put cocaine in its drink when cocaine wasn’t “cocaine.” To oversimplify the answer to whether the business is simple and understandable? Buffett would have probably said “Buy em, they’re selling legal cocaine!”

Well, that’s enough about coke of all sorts. As investors, we fail to buy stocks of businesses we understand because we get caught up in stories which mask underlying factors affecting the bottom line and future of the business. We get caught up in fads, fall in love with a company or the company’s message then blindly follow it even though its product is replicable. Combining the superior product experience with a profitable business model is the main formula to simple and understandable businesses. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t invest in any internet startups – these are relative statements and are taken best within context. If you are well-versed in internet businesses then you will understand how an internet startup will monetize its user traffic better than an engineer who understands the difference between two competing new technologies to power trains. That’s just the first of Buffett’s tenets, but as we move on keep in mind how the tenets are an interrelated chain, rather than an independent checklist.

2. Does the business have a consistent operating history?

3. Does the business have favorable long-term prospects?

Although it seems like a safe bet from the two tenets above, I doublechecked to be sure: WB doesn’t mess with startups. He’s got too much money and not enough time to waste on lottery tickets. Consistent operating history and favorable long-term prospects are directly related to an established successful business in a stable environment. Who better to explain further than Buffett himself in his 1987 shareholder letter…

“Severe change and exceptional returns usually don’t mix. Most investors, of course, behave as if just the opposite were true. That is, they usually confer the highest price-earnings ratios on exotic-sounding businesses that hold out the promise of feverish change. That prospect lets investors fantasize about future profitability rather than face today’s business realities. For such investor-dreamers, any blind date is preferable to one with the girl next door, no matter how desirable she may be.

Experience, however, indicates that the best business returns are usually achieved by companies that are doing something quite similar today to what they were doing five or ten years ago. That is no argument for managerial complacency. Businesses always have opportunities to improve service, product lines, manufacturing techniques, and the like, and obviously these opportunities should be seized. But a business that constantly encounters major change also encounters many chances for major error. Furthermore, economic terrain that is forever shifting violently is ground on which it is difficult to build a fortress-like business franchise. Such a franchise is usually the key to sustained high returns. “

MANAGEMENT TENETS

4. Is management rational?

Management should plan and act like the owners of the company. What exactly does that entail? It means creating value and building a business. It means long-term value creation trumps personal gains (annual bonuses, etc.) or short-term stock performance. These are still very broad/wide-ranging statements so let’s get even more specific with simple technical terms.

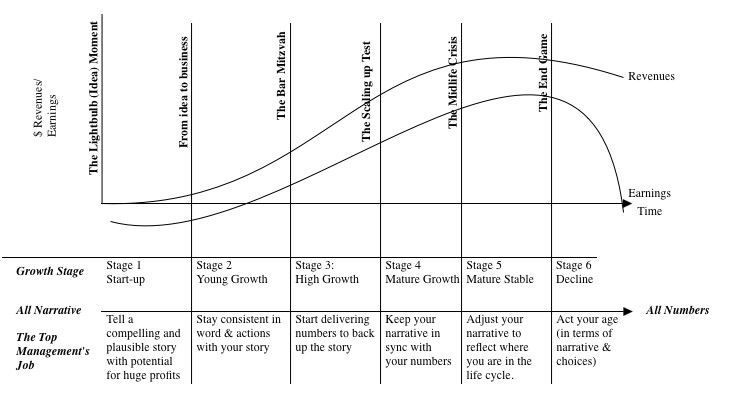

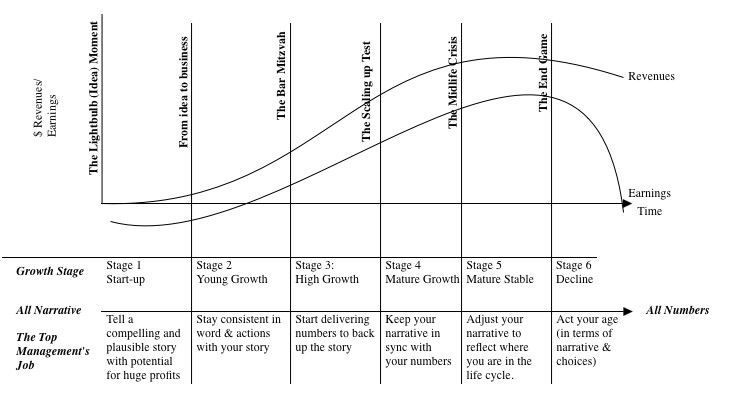

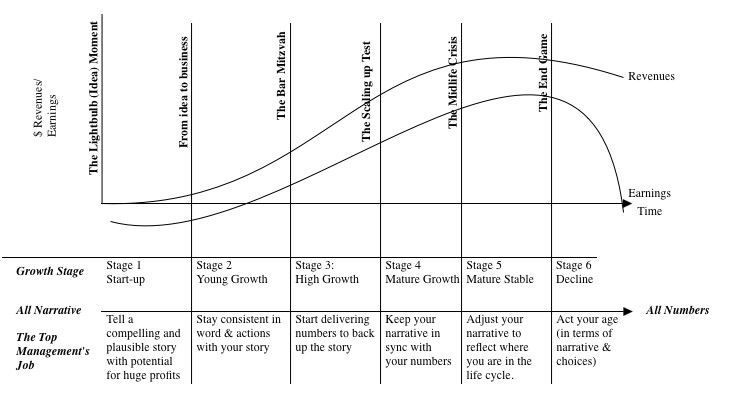

Management needs to make investments at rates of return which are higher than the company’s cost of capital. Over time, investments with returns < cost of capital erode the value of a company, and vice versa. That being said, depending on the stage of a business’s life cycle, management must often consider prudently investing in projects with negative returns. For example, during the early developmental stages, a business may have to establish products and market presence before considering profits. Check out the business life-cycle graphic in Exhibit 1 (brought to you by the great Professor Damodaran). Think about Amazon in this case. Although it’s been around since the 90’s, they are still establishing themselves as a leading retailer by stealing market share from other retailers. This means huge revenues and tiny profit margins. They are still in the Young/High Growth stages where revenues are exploding while they barely break even on the bottom-line.

Figure 1 – Business life cycle – courtesy of NYU Professor Damodaran http://people.stern.nyu.edu/adamodar/pdfiles/country/corporatelifecycleLongX.pdf

In my opinion, even though it doesn’t exactly fit the steadfast “investment returns > cost of capital” mantra, Amazon’s management is rational. They are purposely investing to grab market share instead of driving profits. At the same time, AMZN bears would argue the reverse saying that this market share gain will never be monetized. The AMZN bull vs bear debate is much like WB’s tenet about management’s rationality though – open to opinion.

5. Is management candid with its shareholders?

This one’s pretty simple – is management shady? Management must report every bit of information relevant to shareholders and also report negative news in a genuine manner. If management is rational and acting as a business owner, it makes honesty with shareholders natural. I think of Enron as an extreme example of this gone wrong. It is easy to look back and criticize shareholders for being blind to some obvious red flags, but as far as Buffett’s tenets go, this is probably the most black and white. Check out Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room if you want to read more about one of, if not the greatest corporate failure in recent history.

6. Does management resist the institutional imperative?

Buffett’s last managerial tenet suggests avoiding the easy way out. The institutional imperative is the tendency of corporate managers to mimic the actions of their competitors, even when those actions are destructive or irrational. Managers forego long-term profits just to avoid short-term pain, and this tenet affects industries just as much as companies. Take the American automobile industry. It’s safe to say an oligopoly has existed in America, or at least a duopoly between GM and Ford. I can’t find the chart but I saw it in a magazine (Bloomberg Businessweek maybe, if someone can send me a link?). Anyway, the chart plots miles per gallon (X-axis) vs avg car price (Y-axis), the chart actually made no progression to the right (more MPG) while rising steadily during the 80s-90s. During some prolonged period, MPG actually decreased while prices increased (probably related to truck/SUV growth).

I understand using MPG as a scale to measure industry and company advancements is ignoring a lot, but bear with me for this example. There was almost no progress in MPG until higher fuel standards were introduced by Obama in early 2000’s (don’t quote me on that). Fuel efficiency barely crept up while maintaining bare minimum….until the free market was disrupted. Tesla has disrupted the industry so deeply that each automaker now has plans to roll out electric vehicles (EV) in the very near future, if they haven’t already. Volvo is going fully electric in a couple years! Due to automakers’ complacencies though, they are way behind in technology and can barely provide half of Tesla’s driving mileage/capabilities at more expensive price points.

Was this a ridiculously long tangent about MPG and free markets? No, well maybe some of it was…but we’ll return to the main point. GM, Ford…and basically every automaker in the world showed little, if any, initiative or ambition to improve the consumer’s auto experience – there was no leadership in the industry. Looking back, I’m actually surprised Toyota didn’t go full electric given the cult success of the Prius. The Prius was one of many signs that the technology for EV existed. Exploring those options would have meant R&D spending, hence a hit to current bottom-lines and no immediate reward. Specifically, THAT is an example of management resisting the institutional imperative to buck the trend and lead into more promising initiatives. GM, Ford, and all of the other automakers are keen examples of management resisting the institutional imperative and being complacent. These automobile examples show the effects of management’s inability to establish their company as a leader.

FINANCIAL TENETS

7. What is the return on equity?

Focus on ROE, not EPS. Companies add to their capital base by making money and holding onto it – aka retained earnings. Obviously, any non-suicidal company is going aim to increase overall earnings. Manipulative companies will take measures to increase earnings per share in place of overall earnings though. Usually, this is the effect of an inability to increase earnings. For example, when companies buy back shares, they increase EPS but not earnings. Certain companies may hide declining prospects and worsening conditions by engaging in share buybacks. This doesn’t mean that share buybacks are a negative indicator; I am just using it as one of many examples of how EPS can be manipulated.

Buffett uses a better measure of a company’s performance – return on equity – the ratio of operating earnings to shareholder equity. It measures management’s ability to generate a return on the operations of the business given the capital employed. When calculating ROE and to ensure it reflects the core business operations/capital with little noise, Buffett stresses to value marketable securities at cost, NOT market value (MV is beyond management’s control). He also excludes all non-recurring extraordinary items which are unrelated to the business.

Since Equity = Assets – Liabilities, it’s possible to show a higher ROE while employing an unsafe level of debt. Therefore, we must take note of debt/equity or the leverage ratio (assets/equity…whatever you call it). That being said, a good management team will consistently achieve good returns on equity while employing a manageable debt level. Debt levels vary greatly across industries so the nature of business must be factored into the question.

8. What are the company’s “owner earnings”?

Continuing and building on the aforementioned earnings theme, the ultimate value of any company is its ability to generate a surplus of cash, via earnings. However, a company with high earnings may have a high fixed asset to profit ratio. This means to maintain ongoing business, the company has to dump its earnings into investments just to keep the business running. A simple example of this would be a company which has to buy/replace machines and product inputs each year just to continue producing goods that are the main source of revenues. These capital expenditures will deplete its cash balance going forward. Obviously, this handcuffs the company and just reinforces the inability for the company to exit the vicious circle. The company must drive static earnings to pay for static cost of fixed assets. Buffett takes note of this by relying on “owner earnings” (OE).

OE is calculated by adding depreciation, depletion and amortization charges to net income and subtracting the capital expenditure required to maintain economic position and unit volume. OE reflects the true cash flow position of a company. Some enterprises (like a real estate development for example) require heavy expenditure at the start and very little later on. Others, like manufacturing, require regular expenditure on plant upgrades or the business slips. OE is an attempt to provide a cross industry analysis measure.

9. What are the profit margins?

The paradox exists where managers of high-cost companies tend to continually add to their overheads whereas the managers of low-cost operations take pride in lowering their expenses. Any money spent on unnecessary costs deprives shareholders of extra profits. The reduction of unnecessary expenses is a consistent theme of effective managers. Proper attention to profit margins helps Buffett avoid companies which are complacent to expenses.

10. Has the company created at least one dollar of market value for every dollar retained?

Take this analogy: economic value is to stock market value, as one dollar of retained earnings is to one dollar of stock market value. In other words, over the long term, every dollar of retained earnings will be reflected with a dollar of market value. Just as stock market value will reflect economic value of a company over the long term, it should reflect retained earnings.

To estimate this factor, subtract all dividends from a company’s net income over the last ten years. This is the total retained earnings. Add that figure to the company’s market value at the beginning of the ten year period to get estimated market value. If the company has employed retained earnings effectively, the market value at the end of the ten year period will exceed this estimated market value. If it doesn’t, buyer beware.

VALUE TENETS

11. What is the value of the company?

Buffett calculates the value of a business as the net cash flows expected to occur over the life of the business discounted at an appropriate interest rate. Net cash flows are the company’s owner earnings over a long period. Owner earnings are awfully similar to free cash flows, so you can consider this Warren’s version of a Discounted Cash Flow analysis (DCF). As far as discount rates go, you could use current 10-year treasury rate or even 30-year, but from my knowledge Buffett actually uses 10%. Well, actually let’s throw this quote out there and dig a little deeper:

Charlie Munger said at the 1996 Berkshire Hathaway Annual Meeting: “Warren talks about these discounted cash flows. I’ve never seen him do one.” [“It’s true,” replied Buffett. “If (the value of a company) doesn’t just scream out at you, it’s too close.”]

So, what do we do since WB’s opportunities aren’t going to be an option for us non-billionaires? First, I recommend reading this short article so you can grasp the main idea in calculating the value of a company – https://seekingalpha.com/instablog/5969741-the-value-pendulum/4868716-warren-buffett-use-discounted-cash-flow. Now you see that WB did actually mention 10% (at the very end). I believe this is more of a hurdle rate, as Munger would say. What’s the point in investing in something in which you can’t expect more than 10% annual return. Then again, if he had to compute the Net Present Value of a company, it’s probably not enough of a bargain to consider for Buffett. We can use our measures of discount rates whether 10 year treasury or a 7-8% arbitrary hurdle rates, or whatever – it just matters that we understand the logic behind it, so I don’t want to make this a lesson on DCF’s. This method would help us calculate values of different companies so we can compare them. Also, those familiar with IRR can take this a step further to do the same, considering each method’s limitations (go for CFA Level 1 if this doesn’t make sense and you’re trying to break into the industry).

12. Can the stock be purchased at a significant discount to its value?

Now that we know the company’s value, is the price at a significant discount to value? The greater the difference, the larger the margin of safety (legendary book by Seth Klarman btw – Margin of Safety, actionable trade ideas, and even more in a book that borrows a lot of ideas from MoS – You Can Be a Stock Market Genius by Joel Greenblatt). Buffet generally aims for a 25-percent discount as his margin of safety. Additionally, a well-chosen stock will have sound fundamentals, which over the longer term will lead to an above average growth in the company’s share price.

Takeaways: The 12 tenets are great guidelines, but they are just that. When used with the proper inference and personal spin, they are powerful. As you can tell though, there is a lot left to interpretation or opinion….so, as a recurring theme, there is no magic formula to investing. That reminds me of www.magicformulainvesting.com – by the author of You Can Be a Stock Market Genius, Joel Greenblatt. I’m not endorsing it as a magic formula but it has its merits.

Among dozens of job in the finance sector, which job title deals with finding the intrinsic value and doing the DCF valuation kind of stuff?

Research Analyst – most likely on the buyside where you are trying to invest for a profit. Portfolio Managers in any value fund of course, as well.

I can vouch for this, I’ve analysed stocks based on most of these ^ tenants and none of the equities have failed to return me a positive number, a few being over 100%.